Story of Northern Tibet: Sonam Gongbo’s “coldness and warmth”

2019-11-18 15:01:00 China Tibet Online

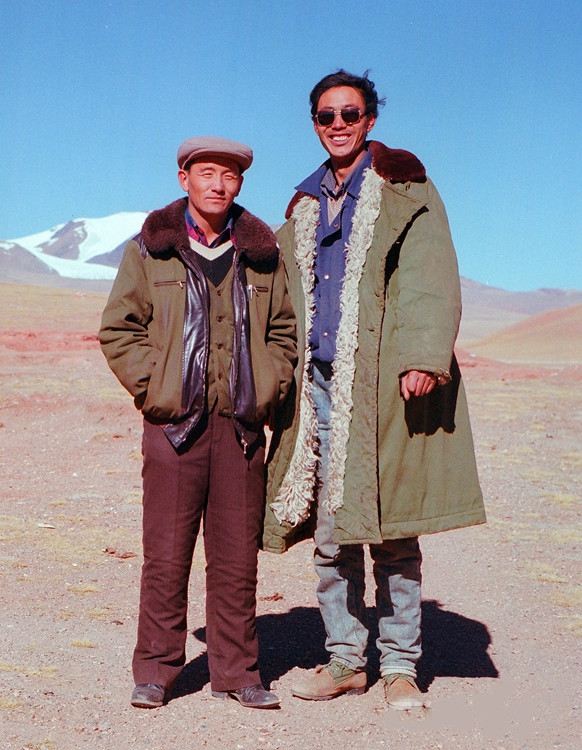

Photo shows Tang Zhaoming (right) with Sonam Gongbo in 1988.

The people of northern Tibet are honest, frank, and straightforward in what they say and do. They don’t talk in a roundabout, indirect way, and they have the same attitude with whomever they are dealing, to such an extent that sometimes there are small misunderstandings.

I and Sonam Gongbo, the former director of the Shuanghu Office in Nagchu City, southwest China’s Tibet Autonomous Region, have a relationship “from cold to warm”.

The first time I ventured into the depopulated zone by myself was during the summer of 1987. He wasn’t at home, so I hadn’t met him, but I had heard about his experience dealing with wild yaks. Before I met him, I imagined that he must be a big, tall, bold, and uninhibited man.

The first time we met was in October 1988 at a meeting in Lhasa. I had heard that someone from the Shuanghu Office had come for a meeting at Lhasa’s Tibet Autonomous Region Hotel, so I went to see.

I had not expected that I would be received coldly by a short Sonam Gongbo.

When he heard that we were journalists who wanted an interview, he stopped us with only one sentence: “There is nothing to report from Shuanghu.” After that, he ignored us and went out of the room by himself.

Fortunately, Secretary Geleg of the Shuanghu Office was also in the room, and he broke the embarrassing atmosphere and explained the situation enthusiastically. Sonam Gongbo came in and out of the room several times. He seemed to have an indescribable anger towards journalists, and in the end, he couldn’t help but interrupt the words of Secretary Geleg: “I don’t have good impression of you reporters. Get out!” In all of our interviews, we rarely come across such an interviewee, and we were surprised at how he ordered us to leave point-blank.

Later, I understood some of his reasons. In 1987, a production team filmed wild yaks in the northern grasslands of Shuanghu. At that time, Sonam Gongbo was the deputy secretary of the Shuanghu Office, and he accompanied the film crew. During the filming, a wild yak got angry and rushed towards the car, and the situation became critical. Sonam Gongbo, who was in charge of the security of the production team, was forced to shoot the yak. Later, one of the photographers with the production team published a photo of the yak that was killed in newspaper after having returned to Beijing, where he called on the whole society to protect wild animals. The one responsible for the whole affair was found to be Sonam Gongbo, and he was very annoyed. “I killed the yak in order to protect their safety, then they turn around and sue me!” He was resentful, and disliked all reporters. His anger was also aimed at us.

The second time I went to the depopulated zone by myself was in November 1988. 36-year-old Sonam Gongbo was the director of the Shuanghu Office. When he saw me this time, hitching a ride into the depopulated zone alone in the winter, he treated me very well. He said that his attitude towards me last month in Lhasa was not good, but now I, the reporter, was “enduring the big box” (sitting in the truck compartment) to run into the depopulated zone, so his view of reporters changed.

The next night, he specially invited me to his room to have a long talk and to apologize for the first meeting in Lhasa. He poured me a cup of wine and invited me to eat the mutton buns he had made. He made a toast, saying sincerely: “As a Xinhua News Agency reporter, your arrival last night moved me!” “You flatter me.” I answered. Sonam Gongbo grew excited, and his voice rose: “A lot of people talk about the changes of Shuanghu, but they don’t dare come here. But you have ridden into Shuanghu twice, which is an amazing thing for a reporter. You are the best friend to Shuanghu.” Without eating, Sonam Gongbo was still happy to drink. He went on to say: “I believe in your perseverance and determination, and I believe you can get results. However, this time you’d better not go into Gacuo Township.” “Why not?” I asked. “Because the altitude is too high, and it is winter, so I’m worried about your health. I can provide you with all the information you need.”

I looked at this Tibetan cadre in front of me, and a warmth filled my heart. But I still told him: “I must see Gacuo Township with my own eyes,” and I explained the importance of investigation as a reporter. Finally, Sonam Gongbo said that he would support me, but he was worried about what I would eat, where I would stay, and my health, and he repeatedly reminded me of that.

Over the next few years, we maintained close ties. In the 1990s, I transferred to Beijing to work. He came to Beijing to get conservation funding to protect wild animals, and I accompanied him to the former State Forestry Administration every day.

About two years ago, we have met at his sister’s house in Qinglong Township, Baingoin County. As soon as he starts speaking, he starts laughing about the past “foolish” events, and he recalls our unforgettable days in Beijing.

Photo shows Tang Zhaoming (right) with Sonam Gongbo in 2012.